Good Lager – a lager that treads lightly

One of our core values at Good Chemistry Brewing is Sustainability. As part of our process of continual improvement in our brewing operations, we wanted to look at how well we are meeting that value. We already use 100% renewable energy at the brewery and The Good Measure, we’ve undertaken an energy efficiency survey, and we regularly consider the ‘big stuff’. So we decided to focus on one beer and look in detail at all stages of production to see how sustainability improvements could be made. For this project we chose our lager and set ourselves the challenge of making it “Good Lager”.

WHY CHOOSE LAGER?

Traditional lager brewing is an energy intensive process. First you have to heat up the wort to boil it for at least an hour. Then you chill it down from 100C to 8C in order to pitch the yeast. The fermentation tank then needs continual chilling during a slow fermentation, around two weeks, to keep it from going above 12C. Finally the beer needs to be chilled right down to -1C for around 30-60 days! You can imagine the energy involved in this when summer temperatures stretch up beyond 30C.

Here at Good Chemistry, we love to drink lager, and we’ve brewed a few over the years, but this is a style and process that evolved when temperature control was down to how cold it was in your caves! We thought that there had to be a smarter way to produce a lager beer in the 21st century, with a process that isn’t so energy intensive, and which uses current knowledge, recent discoveries and modern technology.

There shouldn’t be a need to use so much energy for one style of beer. At a time when we all need to be more conscious of our energy consumption, this is surely an area where we can do things better. A pint of lager shouldn’t need to come with so much embodied energy and such a large footprint. With a bit of thought we should be able to produce this style of beer with a much reduced impact on the world.

So we approached this in a methodical style, as you would expect, first with a LOT of reading and research. This led to our first trials. We broke down the style into the important components, focusing on the finished beer rather than the process involved to get there. So often people revert to the process that goes into making a lager, rather than concentrating on what the finished beer is going to be like.

The conversation around lager brewing often only goes as far as how long it has been stored cold for (the German word “Lagern” means “to store” after all). Elements such as malt flavour, hop aroma, sweetness and bitterness are often lost in the conversation about lager, but these are the real elements that make a style what it is.

SO, WHAT WAS OUR BRIEF?

We knew that we wanted to produce a beer light in colour, with a dry finish, light body and a clear malt flavour. We wanted to start with a grassy, herbal hops flavour, and a neutral almost unnoticeable yeast character. We also wanted the beer to be gluten free and vegan friendly, to remain as accessible as possible (another of our core values is Openness, Accessibility and Inclusiveness).

And we wanted to achieve this with less than half the energy input of traditional methods.

HOW DID WE GET THERE?

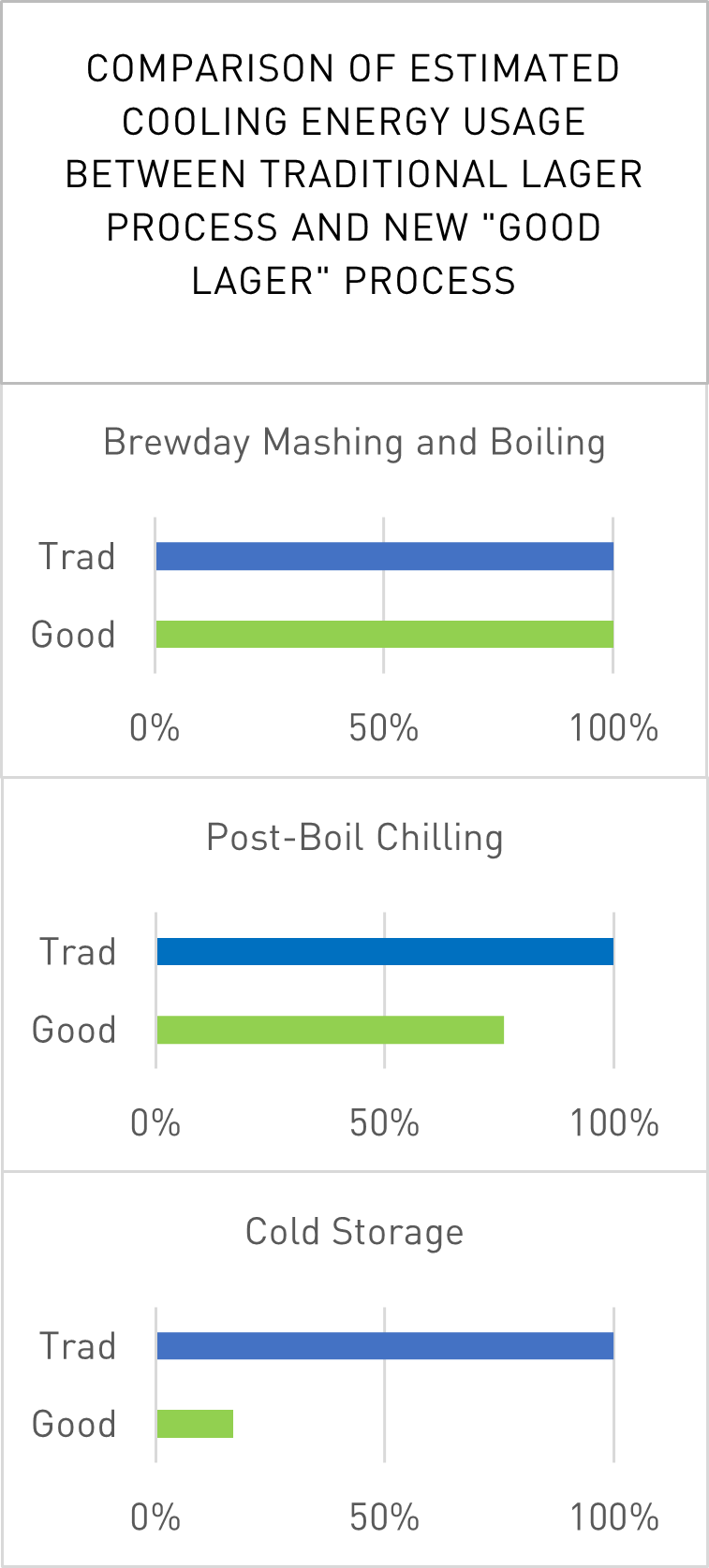

In order to achieve this we needed to identify where the energy inputs were, so we could see where savings could be made. With the traditional lager process, the biggest demand for power comes from the chilling required. This is what sets it apart from brewing other beer styles. So, in order to achieve energy reduction in our lager, we clearly needed to look at how we could reduce the amount of chilling required.

Through our research we identified a group of yeast strains that would ferment very cleanly, like a lager yeast, but would do that at 30C instead of 8C. This yeast strain also produces none of the off-flavours of lager yeast, such as diacetyl or sulphur dioxide, so doesn’t need a long conditioning time.

The first of these yeasts that we trialed didn’t perform as well as we wanted. The fermentation was a bit slow and the flavour wasn’t as clean as we expected. So, we sourced a similar strain from another yeast bank and the results were much improved.

With the new yeast strain we are able to ferment with a clean flavour at 30C, reducing the amount of chilling required on a brew-day as well as reducing the amount of chilling we need to do during fermentation. Because the beer is fermenting above ambient temperature, there is a constant chilling action on the tank from the air, meaning our chiller has to do less work. We have reduced our fermentation time from around 14 days to three days due to the faster acting yeast, further reducing the need for chilling.

We still have to chill the beer to -1C at the end of fermentation in order to allow the yeast to flocculate and to allow us to carbonate and package the beer. However, we only need to keep the beer at this temperature for around five days, instead of 28 or more days.

The process wasn’t the only element of the beer that we considered. In order to reduce the embodied energy in a product you need to take into account all of the ingredients, processes and packaging involved. So we have chosen to use only British grown malt in this recipe, rather than using any continental malts with their increased energy use from shipping. All of our malt comes from Simpsons Malt. One of the major reasons that we use them, beyond the excellent quality of their malt, is their strong sustainability policy and commitment to become carbon neutral by 2030 (https://www.simpsonsmalt.co.uk/sustainability/environmental/).

Brewing beer is still an energy intensive process, but we estimate that we’ve reduced the embodied energy of this beer by 60% through a combination of process changes, ingredient considerations, and changing the yeast strain that we ferment with.

WHAT NEXT?

This isn’t the end of the story for this beer, we intend this to be a process of continual improvement and we’ve already identified some potential areas of improvement:

- We plan to investigate the benefits of using British hops in Good Lager (rather than our current Continental hops) in order to further reduce the impact of transport.

- We will also be looking at how we can improve the recyclability of the packaging we use for our beers. The steel kegs we deliver to pubs (we never package into single use, one-way plastic kegs) will continue to be cleaned and reused, but we want to look at whether we can improve the recyclability of our cans and labels too.

By using this beer as a test bed, we hope to find improvements that we can roll out across our whole range, as part of our commitment to environmental sustainability and continual improvement in reducing our impact on the planet.

We are really pleased with the beer that we’ve produced and proud to be renaming it Good Lager. The process of research, testing and evaluation has been a valuable one, and we look forward to some of the improvements we have identified crossing over to our existing brands and new beers too.

If you have any questions about anything we’ve written here, feel free to drop us a message on social media (@GoodChemBrew) or email us at cheers@goodchemistrybrewing.com. And if you’re from a brewery and you’re also looking at ways to make your operations more sustainable we’d be happy to discuss our experiences.

We look forward to you trying Good Lager (available on our webshop and at The Good Measure now), hope you love it as much as we do, and can enjoy it even more knowing it’s a lager that treads lightly.

Cheers,

Bob & Kelly, and Dan the Brew, Dan No1, Ruth, Lorin and Liam